“Essential self-reliance will come to many…through related efforts of head, hand and heart.”

Custom Textiles began in my parents living room which I converted into my bedroom, office, and sewing area. I was reinventing myself with just a few bucks and the will power to strike out on my own with two elementary school children in tow. I had just dumb confidence to persuade some local designers to hire me for their slip covers and drapes. Quotes were accepted so I had to find studio space in the Collinsville Axe Factory to spread out and set up bigger machines and tables.

I dearly wanted a home of my own and to be with my two children after school. God’s hand of grace knew this even better than I could have imagined. While eating lunch at the popular Lasalle Market I told my story to a realtor who immediately drove me to this small farm house, believing it was a fit for us. Oh, this place looked a mess, with overgrown gardens, fallen trees, and worn out windows, but when I stepped into the stone out-building I believed it was all for us.

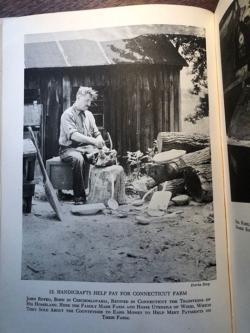

The property has four original structures built by John Royko who started his family and business here 100+ years ago. This is a firsthand interview with John from the 1949 book, Handcrafts of New England:

“John Royko came to America in 1910 from Czechoslovakia. From his wages in a sugar factory, he and his young wife managed to make the first payment on a stoney farm in Connecticut, not far from the village of Burlington. In his homeland John Royko’s father used to make woodenware utensils for his family use and for the people of the countryside. John learned this practical supplementary trade, which helped him pay for his house in America and to rear his family of 9.

He soon rigged up a little sawmill and workshop across the road from the farmhouse, using the engine of a discarded Ford car to run his circular saw. With this he cuts the blanks, which he works up into farm and household utensils of various kinds, about 35 different articles. He said that in Czechoslovakia woodenware was usually not so well finished as the ones he makes here. Customers are willing to pay for nicely shipped articles. Preferably he uses hard maple but sometimes other local woods. Many of his things are made from stumps and large sections of trees, which he shapes with ax, adz, and handsaw. These he later finishes with special cutting tools he makes himself from files, old saw blades and other pieces of good steel.

When the Royko children, 3 girls and 4 boys, were little, they would help their mother smooth and polish the woodenware. Then John, alone or with the children would peddle them around the countryside to sell. This enterprise, together with careful farming of the land, increased the year’s cash income and made it possible to meet payments on the farm during the depression years. Mr Royko also makes straw seats for his chairs (an upholsterer, too!) binds his fence pickets together with wild grapevines, makes his own beehives of straw and perpetuates many other rural practices of the Old World.”

I feel a connection with John Royko, who had survival skills making beautiful things for the home. This property is fresh and useful again. I cleared much of the overgrowth, tilled for vegetable and flower gardens, and restored the machine shop. The 500 square foot studio now has 6 insulated windows, a new door, a floating wood floor over the concrete, a ceiling with lights, and this summer I finished a wall for full length shelves. My sample books are organized, and I can find my supplies. These improvements could not have been possible without the help, and tools, of my dearest friend Len Morneau, who is not only a master craftsman and professional house painter, but generous and patient beyond expectation. My love and gratitude are impossible to express.

Oh, and a farm is not complete without animals, like my Nigerian dwarf goats, Needles, Bobbins, and Camisole!